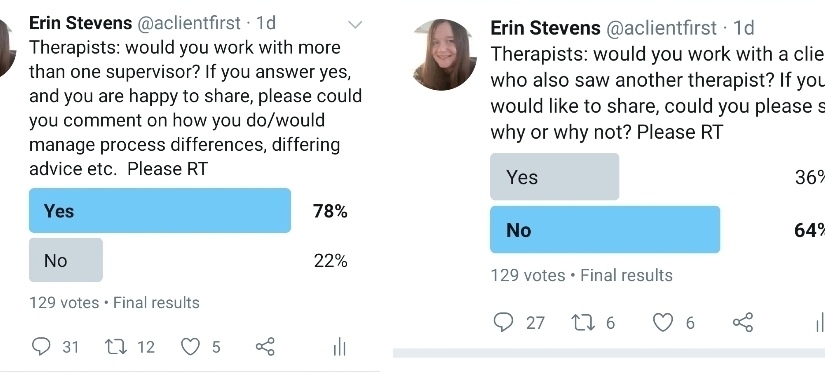

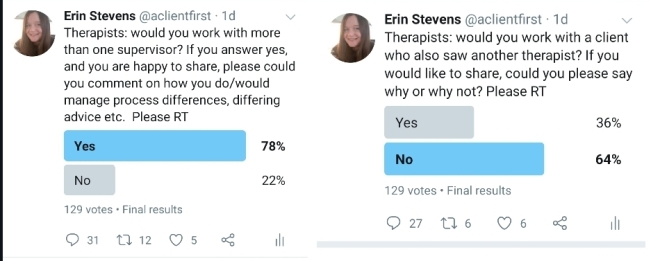

Yesterday I posted two Twitter polls. One asked whether therapists would consider more than one supervisory relationship, inviting comments about how they would manage conflicts of advice, modality etc, and the other asked therapists whether they would work with a client who was also seeing another therapist at the same time. The results are in and show that, of the 129 therapists who voted on the supervisee/supervisor poll, 78% would consider seeing more than one supervisor and 22% would not, whereas on the client/therapist poll, of 129 therapists, 36% would see a client who saw another therapist, while 64% would not.

I posted the polls because I am curious about how other therapists work, and how they conceptualise therapeutic relationships they form with clients and supervisors. I strongly believe in the importance of autonomy, both for therapists and clients. This means that I think it is important that therapists develop their own boundaries (within the bounds of ethical practice, of course) and that clients should be free to either accept or reject the terms that the therapist offers. I think this is the value of a diverse profession – some therapists’ ideas around boundaries will be useful for some clients, and others will be useful for others. Autonomy goes both ways.

While therapeutic and supervisory relationships are not the same, I feel that they are comparable in some respects. They both usually offer holding, space for reflection and are characterised by some kind of process (how this is conceptualised and understood will depend on a range of factors). In the thread below my supervision poll, therapists reported that different perspectives from different supervisors were often useful, and that the therapist themselves were able to make sense of differing advice, and integrate their learning into their practice. Some preferred to keep different client groups for different therapists, and some found taking the same client work to different therapists beneficial. There was a real sense of autonomy, self-trust and learning permeating that thread, I felt.

There was less in the way of consensus on my thread asking about clients with more than one therapist. Some said it would depend on circumstances – for example somebody might want to work on a particular issue with a specialist therapist, or try particular interventions such as CBT or EMDR whilst also seeing a more relational therapist alongside, and that this would be okay. Others theorised that clients wishing to see more than one therapist might be playing out relational enactments, possibly even oedipal in nature. Another simply said “unethical”. Others took a different view, considering the balance of client autonomy, and the potential impact on the therapeutic relationship, or the process. Another said that not ‘allowing’ (my word and my inverted commas!) clients to see more than one therapist seemed like “protectionism” on the part of the therapist.

So what are my thoughts about the questions I posed, and how would I have answered the polls? Well, fundamentally, I believe that there is a richness and dynamic quality to multiple relational dyads in the context of counselling and psychotherapy, and I think this can be true both for therapists as supervisees, and for clients.

Anyone who regularly reads my blog will know I am interested in issues of power in the therapeutic relationship. My interest is piqued immediately when I think about the notion of a therapist ‘allowing’ or ‘not allowing’ a client to do something outside of the therapy hour. Of course, clients are free not to work with a therapist with such a rule, but if the desire to consult with a second therapist emerges some way into the relationship, I propose that it might very much feel that they are being prohibited from doing so, by their therapist.

Are there other circumstances when we, as therapists prohibit clients from doing something outside of the therapy room? All that comes to my mind is that therapies with certain foci, such as self-harm or substance abuse may create ‘rules’ around behaviour outside of the room and these examples seem directly related to the issues the client is in therapy to address (I still think debates could be had about power and autonomy, but perhaps that is for another day).

I can’t think of another circumstance where a client would be explicitly told that the therapist will not work with them if they do a particular thing outside of the therapy room, with their own time and money. For this reason, I am very curious about therapists’ stance on the issue, and the reasons that are given for the choices they make. For example, if, as some therapists believe, the desire to see more than one therapist has its basis in relational patterns or attachment, is there value to allowing it to emerge and working with it? If we believe it might damage the relationship or the process, do we know how? Might it enhance the relationship or process? How do we know? How much of our concern about this scenario has its basis in supposition?

Do we carefully examine our potential discomfort about being talked about to another practitioner? What is our fantasy about our relationship with therapists we don’t know? What about the comparisons that a client would inevitably make about the different styles and personalities of their therapists? How do we feel we would ‘measure up’? I say this without any guesses or judgment about the practices or processes of others. I want therapists to feel free to practice in a way that works for them. But I do think it is important that we consider these feelings for ourselves, especially when we are dealing with the precious and delicate balances of power and autonomy in the therapeutic relationship.

I have two experiences of seeing two therapists at once as a client. The first time, was when I consulted with my current therapist whilst still seeing my previous therapist, with whom I experienced multiple relational difficulties. I knew that my first therapist would not ‘allow’ me to see a second therapist, so I did not tell him. And herein lies a significant issue, for me, with prohibiting the client to do something outside of the therapy room – they might just do it anyway, and if their therapist is unlikely to trust their decision, they are unlikely to trust their therapist with the information. For me, “you don’t trust me, so I don’t trust you” would characterise that first relationship very well. Going to see a second therapist helped me to recognise the multiple abuses which were taking place in my first therapeutic relationship, and I subsequently left and stayed with my current therapist. I am grateful to my current therapist for trusting my process when I came to him and told him that I already had a therapist. Without it, I may have had a great deal more difficulty leaving an abusive therapy situation.

My second experience was relatively recent – I wanted to consult with a second therapist about a particular issue. I didn’t ask my therapist if I could, I told him that I am. I know that he trusts me wholeheartedly to make the right choices, or to learn from it when I don’t. That unwavering trust has been the single most valuable and enduring ingredient in the nurturing and growth of my own self-trust. By gifting me self-determinism at a time I felt unable to take it for myself, I had an opportunity to take ownership of it, and now that I do, will readily gift him a place alongside me to explore it: “You trust me, so I trust you”.

I don’t have any answers, or truths, but, in the spirit of sharing ideas and reflecting on our practice, I offer my own experiences, and questions that come up for me when I hear therapists say that they don’t see clients who see another therapist. I hope this blog post opens up this discussion, and I invite therapists, whatever your policies, thoughts or gut responses, to continue conversations about our boundaries, power in the therapeutic relationship, and how we think about our relationships with clients and supervisors.